This article was written by Hans Lee, originally published by Livewire Markets on 16 March 2023. It is reproduced here in full without amendment with thanks to Livewire Markets.

Analysis conducted for Livewire suggests the great Australian dream is now even more out of reach than previously thought.

At the best of times, buying a first property is hard. For many Australians, (Livewire staff included), scraping together the savings to compile a 10% mortgage deposit is an almost insurmountable challenge. And that’s before servicing interest repayments are even considered.

Now, add to this problem, the 350 basis points worth of rate hikes from the Reserve Bank in less than 12 months….. and it’s no wonder that mortgage stress is at record levels and refinancing in January was the highest on record.

The rate hikes, and the expectation of their impact on mortgage stress, have led to the steepest price falls in modern times, with the CoreLogic five-capital-city metric falling by more than nine percent year-on-year. Normally, this should mean that home buyers get an easier entry point into the market. But these aren’t normal times and the Reserve Bank is not hiking in a normal environment.

So it’s led us to ask a pertinent question: Is Australian property actually less affordable now than before the pandemic?

The answer to this question is the subject of this wire. We’ll also tackle the other question many homeowners have on their minds – is this all Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe’s fault?

The experiment

To answer the key question, we asked the team at Yard Home Loans to work out the change in borrowing capacity between March 2020, just before the first RBA rate rise, and today.

Several assumptions were used, plenty of which will be described in the table below. In all cases, the following was applied.

- 80% LVR

- The borrower rate is 2.25% + cash rate.

- APRA buffer of 3%, which changes over time

With that said, these are the results of our experiment. Of course, this isn’t the case for everyone but it’s an illustration of how borrowing capacity has changed in the last three years. The data was provided by Toby Boswell from Yard Home Loans.

| Case | March 2020 | April 2021 | Today (March 2023) | % Change |

| 1 | $510,000 | $530,000 | $405,000 | -24% |

| 2 | $980,000 | $995,000 | $760,000 | -24% |

| 3 | $850,000 | $890,000 | $540,000 | -39% |

*Case 1: Single 30-year old with no dependents, earning a full-time $90,000 wage with $25,000 in HECS debt to pay off.

*Case 2: A young married couple with two dependents, earning $100,000 and $50,000 respectively. Neither have any HECS debt remaining.

*Case 3: 60-year old couple with no dependents, $140,000 and $40,000 wages respectively. They already own an existing home ($200,000 left on mortgage) and are looking to buy an investment property attracting 4% rental yield.

**All numbers are indicative only.

How did we get here?

Interest rates and inflation is the simple answer. After all, in the last 12 months, the average repayment for the standard $1 million loan is up by more than $1,800 per month. But in truth, a lot of other changes have been quietly taking place behind the scenes.

“Other factors such as buffer rates, increased benchmark expenses, and changes to tax have had minor impacts but have also contributed to an overall decrease in borrowing capacity from its peak at the start of 2022,” Boswell noted.

CoreLogic’s Head of Australian Research Eliza Owen actually goes one step further arguing every major affordability metric has declined in the last five years. Owen puts the blame on mortgage serviceability.

“Mortgage serviceability is fast becoming the most prominent challenge in housing affordability. While our affordability metrics are a bit lagged, measures were already showing a rapid deterioration late last year,” Owen said.

At the rental level, things have soured but not as much at least on the data.

“Rental affordability at the median household income level has worsened, but doesn’t look as severe as mortgage serviceability,” Owen said.

But was it always unaffordable?

Philip Ryan of Trilogy Funds pins the problem on a combination of rapidly rising rates, a lack of new housing supply, and anaemic wage growth (or in this high-inflation era, real wage losses).

“These periods of time do repeat themselves but this one will be traced to interest rates and a lack of supply,” he said. “I also suspect we will continue to see this problem persist until we start to see wage growth. The one rider on that is people now have so many more opportunities to multiply their income,” he added.

Ryan also has another view – Australian property was actually always unaffordable.

“If it was easy, wouldn’t a lot of people have more than one house?,” Ryan quizzed. “If it was really affordable, we’d all have 10 houses!”

But he doesn’t deny the last five years have made things much, much harder.

“In the last 12 months, interest rates have gone up markedly and first home buyers now have 30% less purchasing power,” Ryan said.

Does the RBA deserve all the blame?

Our man at Yard informs us that depending on circumstances and the size of the loan, a 0.25% rate hike could trim between two and four percent (2-4%) off your borrowing capability. So had the RBA started hiking interest rates earlier, could this crisis have been lessened or mitigated?

Yes and no.

“The RBA was highly stimulatory and the Government was also highly stimulatory during COVID’s outbreak,” Ryan noted. “In many ways, what they did was the right thing to do. Otherwise, we could have ended up with another Great Depression,” he added.

But they were tripped up by Governor Philip Lowe and the forward guidance which later proved to be the opposite of prescient.

“The RBA is forever trying to do its job in the rear view mirror,” Ryan said. “I can understand their position being complicated and difficult but a rapid change in rates has exaggerated the problem,” he added.

Where will house prices go from here?

Ryan’s base case – which in turn leans bullish – suggests the seeds for the next property boom are being sown now.

“We have reduced building activity, some builders have collapsed, and there are difficulties with trades and council approvals. There is a real lack of product supply coming to market,” Ryan said.

Ryan goes on to add that while achieving the terminal rate is important, he also believes there should be an inflection point when it comes to continually increasing rents. His view is that the next boom will occur when first home buyers decide it’s cheaper to buy than rent and when investors are drawn back into the housing market because of increased rents.

Owen is less sanguine, arguing the ‘bottom’ is likely going to be dependent on how fast the RBA transmission mechanism does its job.

“We are hesitant to say whether the bottomed out however, because interest rates have further to work their way through to borrowers and mortgage holders, and this dampener could be compounded by a looser labour market in 2023,” she says.

As for the top markets where the buying may restart, she points to Western Australia, the Top End, and the leafy suburbs of Sydney.

“Our expectation is that regions with favourable migration trends and strong rent return, including resource-based markets across WA and the NT, will have mild declines through this cycle,” Owen said.

“On the east coast, it is expected that desirable, high-end owner-occupied markets will be the first to show signs of recovery, such as the North Sydney and Hornsby market of Sydney, where large family homes have seen relatively sharp price falls, and may become appealing to buyers once interest rates stabilise,” she added.

One last thought

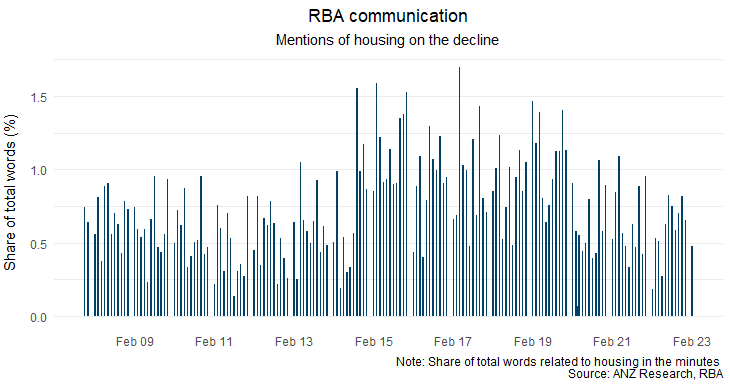

We were talking earlier about the Reserve Bank and whether specifically all the blame should be put on Phil Lowe. Well, if the RBA’s communication is anything to go by, perhaps not. This chart from John Bromhead at ANZ finds that mentions of housing have declined in recent years – which must go some way to explaining what the RBA is more focussed on.

If inflation comes down and the RBA reaches its terminal rate, it’ll be interesting to see if these mentions tick back up.

Related Articles: